As a reaction to my recently published IT case study I received many mails which confirmed my experiences and asked for more examples. That doesn’t imply representativeness, but it shows that such cases are not the exception. Together with representative research about Project Management like the Standish Group Chaos Reports or PMI’s Pulse of Profession we can imagine how much money is burned repeatedly in badly managed projects. Totally unnecessary, as again shown in the following case from my practice:

The case:

The case:

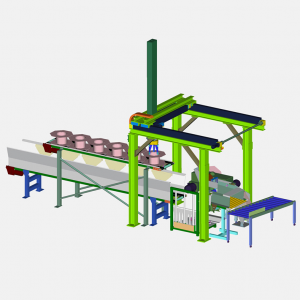

An SME plant engineering company, after decades of uncontested market leadership, faced a growing low-price competition from foreign countries since some years. The order books were still well filled; the firm was comfortably equipped with private capital. Still customers increasingly discussed prices and didn’t accept delays at the contract fulfilment any more. The company had invested in several R&D projects for retaining technology leadership to differentiate from the price fight and to decrease product costs. Most of them were far behind schedule and over budget. In addition clearing and settlement of contracts were slowed down repeatedly in own plants, at suppliers and during installation.

The management already had engaged a number of consulting firms to perform rationalization and process optimization projects. But it took until a key product development project with a schedule delay of 1½ years was jeopardized to completely loose its time-to-market and therefore its ROI that management determined to conduct a project revision and recovery action.

My expert assessment’s findings:

After roughly four weeks my diagnosis was firm. This is the short version:

In product development top-class engineers were working in multiple projects at a time, led by chief engineers who had special expertise in the specific development field, but did the project management by the side and without explicit education. Their focus naturally was on the technique; problems seemed solvable as long as time and money did not matter. In the Steering Committee there was no agreement on priorities of the goals “unchallenged technology” vs. “product cost cuts”.

Instead of giving direction by decisions, they issued increasing caveats, and swallowed increasing surplus cost for a long time. In the projects development phases and prototypes frequently were delayed, personnel and machines for tests and dry runs were ordered, cancelled, and then were not available for the new dates, etc. “Lack of resources” was the prevalent opinion, but in fact there was a lack of leadership and of a reliable planning and control, spiced with overload and inefficient multitasking.

With a clear, unambiguous scope many tasks wouldn’t have led to conflicts, the majority of the tests could have been conducted in the laboratories prior to building expensive prototypes, and thus could have eliminated a lot of reservations and risks upfront. The Steering Committee could and should have intervened much earlier if they had had a proper reporting and a sense for their own project responsibility.

The complete lack at all levels of project management and understanding for project roles in R&D prompted similar deficits at the company’s delivery projects.

Root causes are in the corporate project management culture

The project leads there had the difficult task to coordinate the assembly in the P&L responsible plants, the shipping, and the installation  onsite at the customer without having real competences and access to resources. Sales, driven by commission interests, often threw badly cleared orders and unrealistic delivery promises over the fence at the projects. At the installation sites, in particular with international orders, regional sales interests, mentality or working habits frequently spoiled fulfilment to plan. Suppliers and customers often had a weak organizational maturity to achieve provisions as planned. Thus many projects were “deeply red” already at order confirmation; the involved units’ own lives prevented from targeted project management, and their individual striving for profit made an overall optimization of project margins impossible.

onsite at the customer without having real competences and access to resources. Sales, driven by commission interests, often threw badly cleared orders and unrealistic delivery promises over the fence at the projects. At the installation sites, in particular with international orders, regional sales interests, mentality or working habits frequently spoiled fulfilment to plan. Suppliers and customers often had a weak organizational maturity to achieve provisions as planned. Thus many projects were “deeply red” already at order confirmation; the involved units’ own lives prevented from targeted project management, and their individual striving for profit made an overall optimization of project margins impossible.

The conclusion was that in both areas not the project leads and teams were the root causes for the misery but insufficient sensibility and recognition for project work and management in the entire company. Besides recovering the R&D key project I therefore had to initiate a successive change in the organizational project culture, away from functional thinking in products towards a holistic customer focus in a project-driven business. (This btw. nicely shows the strategic business component in my professional work …)

The first could quite immediately be managed with some organizational measures, some fundamental decisions about the project’s targets, and a little grab in the project management processes and tools box. After roughly half a year the project was completed with a marketable result; a follow-up project was initiated to further improve the technology.

The project’s distress total balance:

- Delay ca. 8 FTE x 1,5 man years = 650,000 Euro

- Effort until completion another 8 x 0,5 man years = 200,000 Euro

- Effort for revision and recovery ca. 30,000 Euro

or in other terms

- Surplus cost in total ca. 880,000 Euro (planned budget 750,000 Euro)

- Revenue loss ca. 200 units not built/sold in 1.5 years = 60 Mio. Euro

The company’s “cultural change” is still going on, after management had struggled hard to acknowledge its necessity. Culture is something that has grown and is established, habits of thinking and acting cannot be changed that easy. But if there is to be profit again in the corporate balance instead of a red Zero, if with customer orders (= projects) profits are to be made instead of only turnover, then this effort is a strategic imperative and economically reasonable. To wait would mean to further lose money and market share.

Learn more about the topc Project Recovery…

Pingback: Why Projects fail